Nations: Mania: Name

Nations: Mania: Name Nations: Mania: Name

Nations: Mania: Name My notion of a personal, independent state has gone under a number of different names since I conceived of the People's Republic of Somewhere Else as a child.

My notion of a personal, independent state has gone under a number of different names since I conceived of the People's Republic of Somewhere Else as a child.

For the story of its inception, the various names under which it went, plus colourful pictures, and lots of exciting words including fascists, chorizo, and crustaceans, consult the history of Mania.

An ancient Greek:

An ancient Greek:

quite possibly the one who

invented the 'ia' endingThe name Mania was derived very simply, from the stem of the name 'Manny' (or 'Manuel') - Man - and the Greek affix ia meaning 'state or quality of'.

In fact, ia is easily the most popular affix to the names of established states. Of the 191 member states of the United Nations, 36 - that is to say nearly one in five - use it, these being:

Albania, Algeria, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Cambodia, Colombia, Croatia, Estonia, Ethiopia, Gambia, India, Indonesia, Latvia, Liberia, Lithuania, Malaysia, Mauritania, Micronesia, Mongolia, Namibia, Nigeria, Romania, Saint Lucia, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Somalia, Syria, Macedonia, Tunisia, Tanzania, and Zambia.

(It has since been pointed out to me that these are just those which end 'ia' in English. More do in their own languages, such as "Italia". Bugger.)

Queen of Narnia (left), & Chief Narn (right): see what I mean?Were such affixes, say, a firm of management consultants (a dizzying concept, but stick with it), ia would be so senior a director that he could afford to habitually park in land's parking space (only 9 lands in the UN), and feign to forget stan's name altogether (only 7 stans), and they would be forced to endure this treatment, and compensate themselves by sleeping with ia's wife - whose reasons are her own, and outside the scope of this metaphor. I will not descend into gossip.

Queen of Narnia (left), & Chief Narn (right): see what I mean?Were such affixes, say, a firm of management consultants (a dizzying concept, but stick with it), ia would be so senior a director that he could afford to habitually park in land's parking space (only 9 lands in the UN), and feign to forget stan's name altogether (only 7 stans), and they would be forced to endure this treatment, and compensate themselves by sleeping with ia's wife - whose reasons are her own, and outside the scope of this metaphor. I will not descend into gossip.

Where was I? Oh yes. Personally, I just like the sound of ia. Consider C. S. Lewis's Narnia, for instance. There is something faintly odd about Narnland: being the King of such a place would seem only to make one the 'Chief Narn': and that's not a title I can see children yearning for. Similarly, Thomas Moore's Utopistan has quite other connotations.

"I am a free man!"Though the derivation 'Manny - ia' first suggested the name of Mania, the name was chosen as much for the further layers of meaning it suggested.

For instance, the stem 'Man' might also represent not Manny, but any one man. In this case, 'man - ia' would mean simply 'one man's country'.

Or if all the talk of Greek seems fanciful, 'man - ia' can also be colloquially read as "man 'ere".

Alternatively, as the only citizen of Mania I might sign myself 'man 1a': fans (like myself) of Patrick McGoohan's brilliant and extraordinary series The Prisoner might recognise the idea.

But aren't I omitting the plainest alternative meading of 'Mania', that of 'madness'?

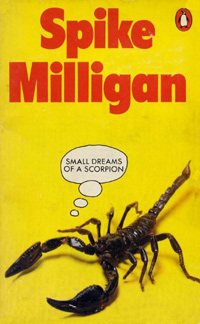

Small dreams of a scorpionAs a boy I was a huge fan of Spike Milligan. His name on the cover of a book was sufficient to ensure that I would read every word. This is important, because the book in question was Small Dreams of a Scorpion, and it was a book of poetry. Not funny poetry, which I liked, but what I called then, and still call, real poetry: no laughs, just lines that didn't reach the edge of the page. Nothing but his name on the cover would have induced me to read such a book. I wish I could say this was a childhood prejudice, soon grown out of, but it is not so: I still read very little poetry, and with a few important exceptions, care for it even less than I did then.

Small dreams of a scorpionAs a boy I was a huge fan of Spike Milligan. His name on the cover of a book was sufficient to ensure that I would read every word. This is important, because the book in question was Small Dreams of a Scorpion, and it was a book of poetry. Not funny poetry, which I liked, but what I called then, and still call, real poetry: no laughs, just lines that didn't reach the edge of the page. Nothing but his name on the cover would have induced me to read such a book. I wish I could say this was a childhood prejudice, soon grown out of, but it is not so: I still read very little poetry, and with a few important exceptions, care for it even less than I did then.

But Small Dreams haunted me. I have long since lost my copy, and had to search the web for the cover picture illustrating this page. I wasn't ready for the chill it gave me when I found it, and suddenly - vividly - I remembered the day I first read these poems, tucked in the corner of my bedroom as night was falling.

"The young boy stood looking up the road to the future. In the distance both sides appeared to converge together. "That is due to perspective,when you reach there the road is as wide as it is here", said an old wise man. The young boy set off on the road, but, as he went on, both sides of the road converged until he could go no further. He returned to ask the old man what to do, but the old man was dead."

Poems like this affected me not because they bought some new horror, but precisely because they caused the same objectless fear, the same empty feeling in my chest, that I already knew so well. I suffered then, as I do now, from depression - severe, recurring, and cyclic - but I had discussed it with noone. For the first time, I realised that I was not alone: whatever I had, Spike had it too. It helped.

Spike Milligan

Spike Milligan

Minister for Laughter and TearsIt was describing Spike Milligan that I first heard the term manic depression (the old name for bipolar disorder), and I remember feeling, without fully understanding, that if it was good enough for him, it was good enough for me. It was a small act of bravado against feelings which frightened me, and prejudices around me even worse then than they are now. It is perhaps partly in a similar spirit of defiance that I embrace the name Mania now: manic and proud!

As a small acknowledgement of the role Spike has long since played in my life, he is now officially Minister for Laughter and Tears in the Manic government.